Traits

Traits are halfway between Java interfaces and abstract classes.

· Like abstract classes, traits may contain concrete members, but may not be instantiated.

· As with interfaces, a class can inherit the members of multiple traits.

· Classes can extend traits

class C extends Trait1 { ... }

· Traits can extend classes and other traits

trait T1 extends Class1 { ... }

trait T2 extends Trait1 { ... }

· Classes, objects, and traits can mix in traits

class C extends Trait1 with Trait2 with Trait3 { ... }

val obj = new Class1() with Trait1 with Trait2 with Trait3 { ... }

Example: A Scala

Reference Interpreter for the Alpha Language

Here's a test-driver for Alpha:

object TestAlpha extends App {

var exp:

Expression = Sum(Number(42), Product(Number(3.14), Number(2.71)))

println("value = " + exp.execute)

exp = Product(Number(2),

Product(Number(3), Number(5)))

println("value = " + exp.execute)

}

It produces the output:

value = Number(50.48)

value = Number(30.0)

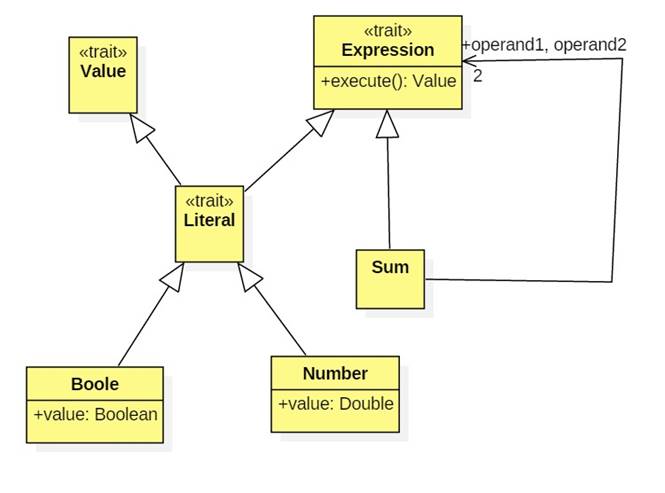

Here's a partial design of Alpha:

Like most programming languages, Alpha distinguishes between expressions (things that can be executed) and values (results of executing expressions). Scala formalizes this distinction by defining two traits:

trait Value

trait Expression {

def execute: Value

}

Numbers and Booles are both, expressions and values, When executed they return themselves! In future versions of Alpha there may be additional expression-value hybrids such as strings and characters. Alpha calls all such hybrids literals:

trait Literal extends Value with Expression {

def execute = this

}

class Number (val value: Double) extends Literal {

override def toString = value.toString

}

object Number {

def apply(value: Double) = new

Number(value)

}

class Boole (val value: Boolean) extends Literal {

override def toString = value.toString

}

object Boole {

def apply(value: Boolean) = new

Boole(value)

}

By contrast, a sum is an expression but not a value:

class Sum(val operand1: Expression, val operand2: Expression)

extends Expression {

def execute = {

val arg1 = operand1.execute

val arg2 = operand2.execute

if (!arg1.isInstanceOf[Number] ||

!arg2.isInstanceOf[Number]) {

throw new Exception("sum

inputs must be numbers")

}

val num1 = arg1.asInstanceOf[Number]

val num2 = arg2.asInstanceOf[Number]

new Number(num1.value + num2.value)

}

}

// and a companion object

object Sum {

def apply(operand1: Expression,

operand2: Expression) = new Sum(operand1, operand2)

}

Example: Delegation

Chains

Delegation chains are useful when we want to add behavior to an object.

Assume Delegate is a trait with a concrete do-nothing method:

trait

Delegate {

def delegate() {}

}

An

Entity class inherites the do-nothing delegate method, which it calls:

class

Entity extends Delegate {

def doSomething() {

println("calling Entity.doSomething")

delegate()

}

}

Next

we define three sub-traits. Each prints a unique message, then calls

super.delegate:

trait

Delegate1 extends Delegate {

override def delegate() {

println("calling

Delegate1.delegate")

super.delegate()

}

}

//Delegte2,

Delegate3, etc.

Scala

allows objects to inherit from traits, too:

val

test1 = new Entity() with Delegate1 with Delegate2 with Delegate3

test1.doSomething()

val test2 = new Entity() with Delegate3 with Delegate1 with Delegate2

test2.doSomething()

Here's

the output. Note the delegation order:

calling

Entity.doSomething

calling Delegate3.delegate

calling Delegate2.delegate

calling Delegate1.delegate

calling Entity.doSomething

calling Delegate2.delegate

calling Delegate1.delegate

calling Delegate3.delegate